Updated: 2026-01-08

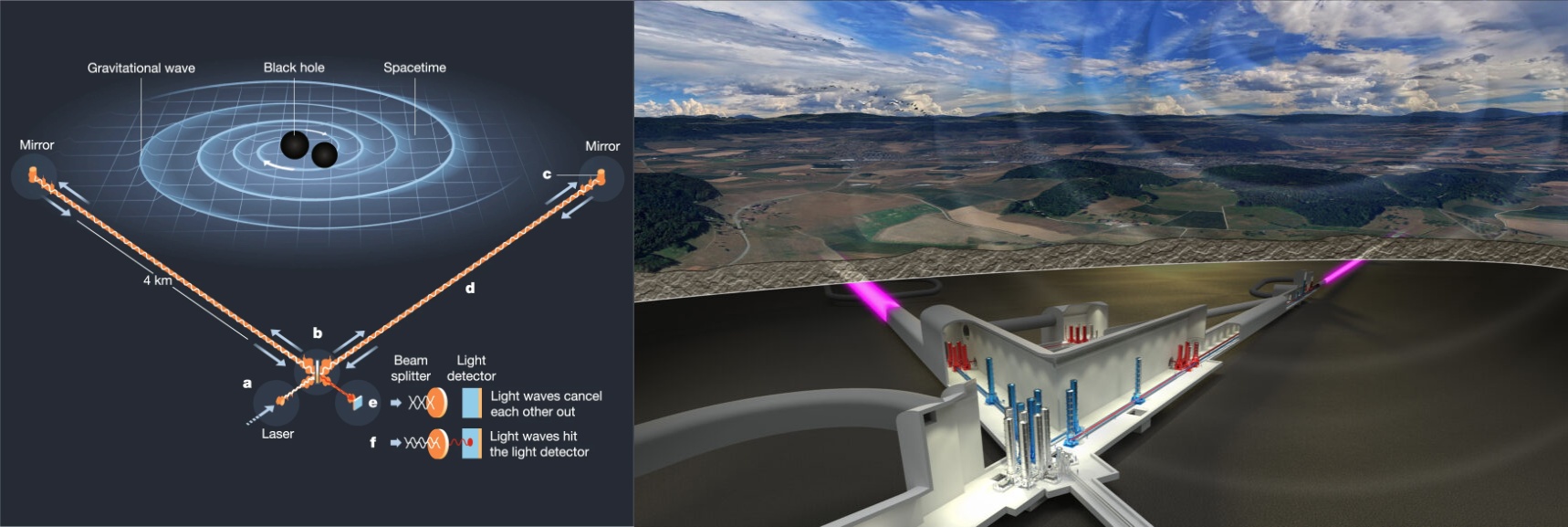

A gravitational wave is a ripple in the fabric of space and time,

created when massive objects such as black holes or neutron stars

accelerate or collide. These waves travel across the Universe at

the speed of light, stretching and squeezing space itself as they

pass. Predicted by Albert Einstein in 1916 as part of his General

Theory of Relativity, gravitational waves were first directly

detected a century later, in 2015, by the LIGO observatory. Their

discovery opened a new way of observing the cosmos — not through

light, but through the vibrations of spacetime — allowing

scientists to study some of the most energetic and mysterious

events in the Universe.

The Einstein Telescope (ET) is a planned European third-generation

gravitational-wave observatory that will take this new field of

astronomy to the next level. It will consist either of a

triangular-shape geometry or two separated L-shape arms geometry

placed in underground tunnels, each about 10 kilometres long,

housing ultra-sensitive laser interferometers. By operating deep

underground and at cryogenic temperatures, ET will be able to

detect much weaker signals than current instruments, observing

black hole and neutron star mergers from the farthest reaches of

the cosmos.

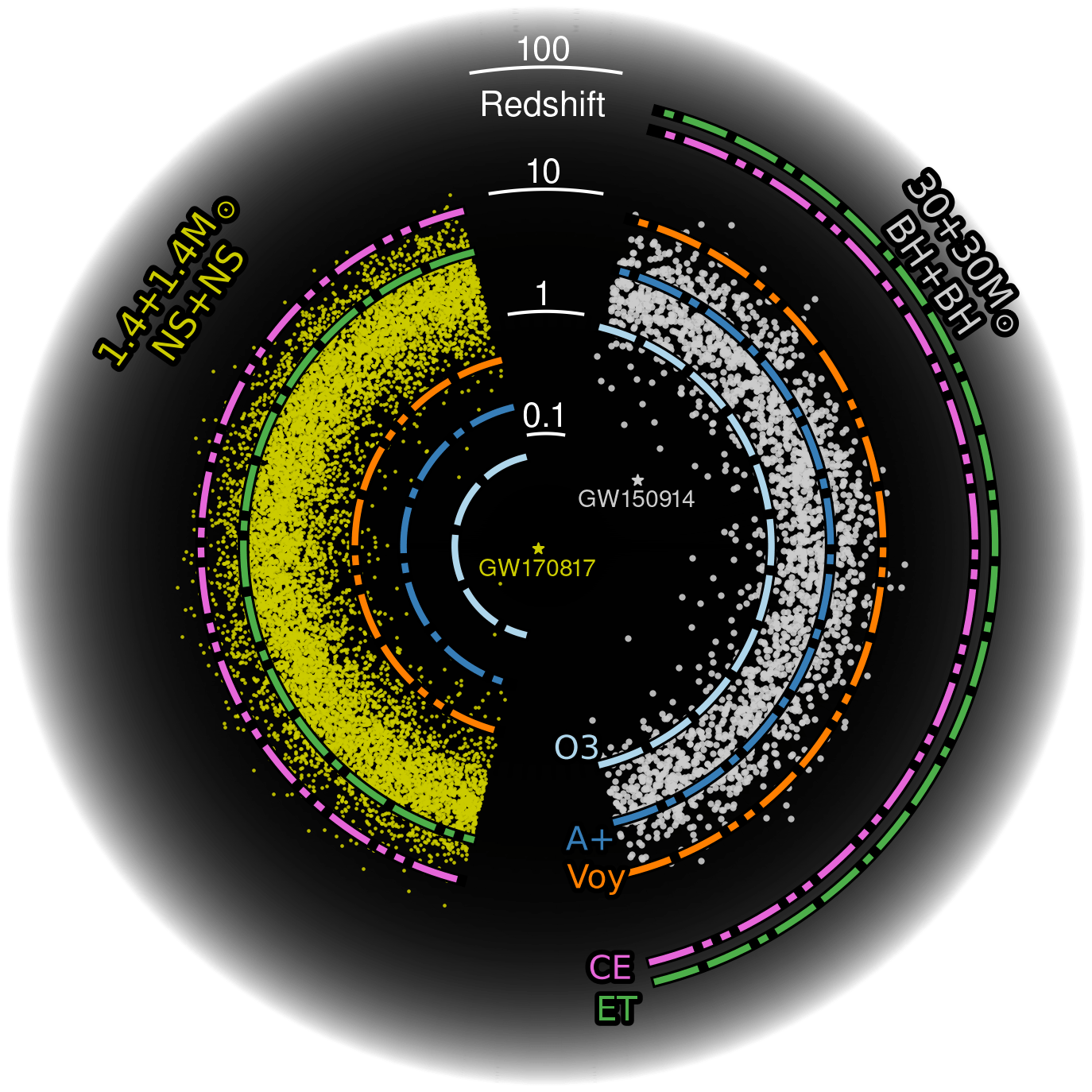

Figure 1: Astrophysical horizon of current and future

gravitational-wave detectors. This diagram compares the reach of

current detectors (like Advanced LIGO A+ and Advanced Virgo) with

proposed next-generation detectors such as Cosmic Explorer (CE)

and Einstein Telescope (ET). The radial axis indicates redshift,

showing how far into the universe different detectors can see

binary black hole (BH+BH) and neutron star (NS+NS) mergers.

GW150914 and GW170817 represent the first observed binary black

hole and binary neutron star mergers, respectively, serving as

benchmarks. Next-generation detectors like the Einstein Telescope

are planned to have a cosmological reach, capable of detecting

sources across the entire universe.

Credit:

Cosmic Explorer Project

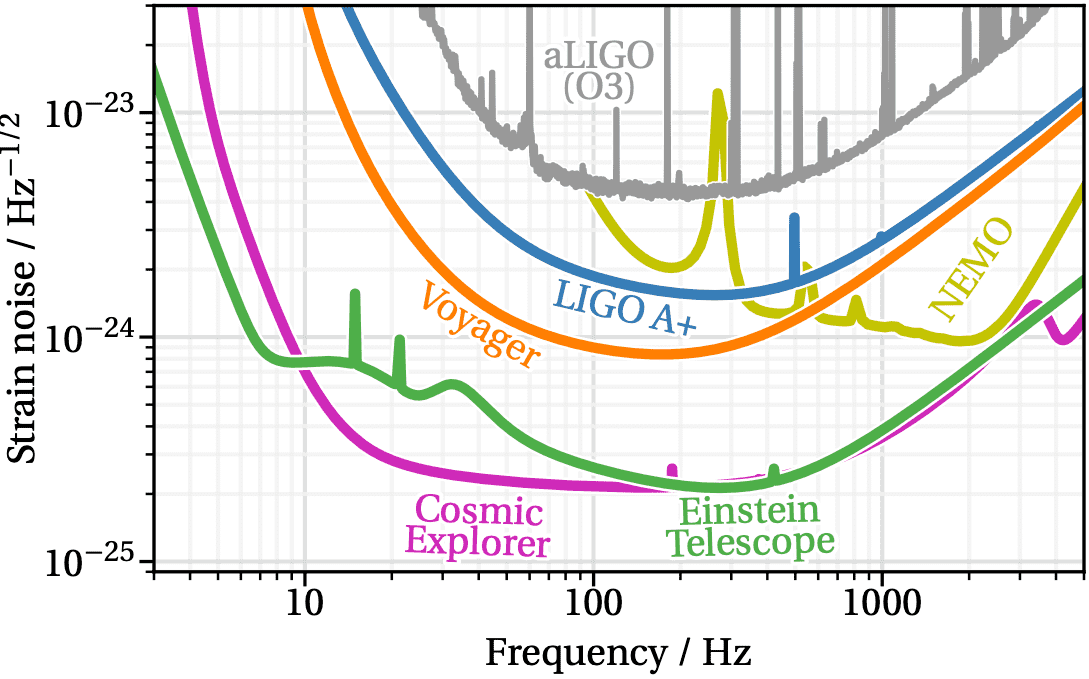

Figure 2: Astrophysical sensitivity (amplitude spectrum of the

detector noise) as a function of frequency for Cosmic Explorer,

the third observing run (O3) and upgraded (A+) sensitivities of

Advanced LIGO, LIGO Voyager, NEMO, and the Einstein Telescope.

Credit:

Cosmic Explorer Project

The Einstein Telescope will consist of a triangular underground

observatory with sides 10 kilometres long. Each side will host two

laser interferometers arranged in an “X” configuration. By

measuring minute changes in the distance between suspended mirrors

at the ends of these arms — as small as one thousandth of the

diameter of a proton — ET will detect passing gravitational waves.

The design includes two sets of interferometers: one optimized for

low frequencies (using cryogenically cooled mirrors to reduce

thermal noise) and another for high frequencies, allowing the

observatory to cover a broad range of sources and timescales.

The observatory will be built deep underground to minimize the

effects of seismic vibrations and environmental noise. Three

potential sites are currently under study: one in Sardinia

(Italy), another one in the Euregio Meuse-Rhine region, located at

the border of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany whereas the

third one is Lusatia in Saxony, Germany. The final choice will

depend on detailed geological, environmental, and logistical

evaluations.

The Einstein Telescope will be about ten times more sensitive than

current detectors such as LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA. This higher

sensitivity will allow scientists to observe thousands of

gravitational-wave events every year, reaching back to the time

when the first stars and galaxies were forming. It will make it

possible to perform precise measurement of neutron star

properties, tests of Einstein’s theory of General Relativity under

extreme conditions, and the search for primordial gravitational

waves that carry information from the earliest moments after the

Big Bang.

The Einstein Telescope will also work in close connection with

other astronomical observatories to form part of the global

multimessenger network, linking gravitational-wave detections with

observations of light, neutrinos, and cosmic rays. Such combined

observations will help identify the origins of the most energetic

phenomena in the Universe, from gamma-ray bursts and magnetar

flares to the merging of compact stellar remnants.

A recent ET Collaboration white paper (see

The Science of the Einstein Telescope, arXiv:2503.12263) outlines in detail the scientific reach of ET: across

astrophysics, cosmology, fundamental physics and nuclear matter

under extreme conditions. The document studies both the proposed

triangular single-site and dual L-shaped geometries, and

emphasises how ET will form a key node in the global

multimessenger network — enabling multi-band gravitational-wave

observations and combining them with electromagnetic, neutrino and

cosmic-ray signals. It also highlights the major data-analysis

challenges ahead, given the high event rates and precision

expected for a third-generation detector.

In addition, a proposed ET U.S. counterpart third generation

ground-based gravitational wave observatory, the Cosmic Explorer,

will have a considerable detection frequency overlap. It will

effectively act as a "Super-LIGO" that scales up current

technology, its arms will be 10 times larger than LIGO’s, i.e., 40

km long. As a result, the two gravitational wave detectors will

act as two distinct halves of a single global observatory. The

Einstein Telescope will play the role of a Woofer because it will

be underground and will use cryogenic (super-cooled) mirrors, it

will be immune to the surface seismic noise that plagues other

detectors. It excels at low frequencies (below 10 Hz). The Cosmic

Explorer will play the role of a Tweeter because it will be placed

on the surface with massive 40 km arms, it will sacrifice

low-frequency sensitivity for incredible high-frequency (above 100

Hz) sensitivity.

The primary research purpose of the Einstein Telescope is to serve

as a time machine for the universe, dramatically extending our

observational horizon to the very edge of the cosmos. Its special

low-frequency sensitivity is crucial because it allows the

detector to observe much heavier objects, such as

intermediate-mass black holes, and to track binary systems for

hours or days before they merge. Scientifically, this enables a

complete census of black holes throughout cosmic history, allowing

astronomers to observe the birth of the very first black holes

formed in the early universe and understand how they evolved into

the supermassive giants found at the centers of galaxies today.

Beyond mapping the history of the universe, the Einstein Telescope

acts as an extreme physics laboratory designed to test the

fundamental laws of nature under conditions that cannot be

replicated on Earth. One of its key scientific goals is to study

the behavior of matter at supranuclear densities by analyzing the

precise properties of neutron stars during a merger thereby

revealing the equation of state for the densest matter in the

universe. For the same purpose, neutron star oscillations, the

formation of stellar black holes, and supernova explosions will be

targeted by the ET. Furthermore, the telescope will perform

high-precision tests of General Relativity in the strong-field

regime, essentially checking if Einstein's theory holds up near

the event horizons of black holes, while simultaneously providing

independent measurements of the universe's expansion rate to help

resolve current tensions in cosmological models. The ET will aim

at detecting the cosmological gravitational wave background

created by phase transitions, cosmic strings or quantum gravity

effects occurring through the evolution of the early universe. In

addition, it shall probe the possible creation of primordial black

holes following the aforementioned phase transitions, which could

have impacted the stellar population dynamics and evolution of

galaxies.

The observatory will be built deep underground to shield it from

surface vibrations and environmental noise. Two possible locations

are currently under study: the Sos Enattos site in Sardinia

(Italy) and the Euregio Meuse-Rhine region on the

Belgium–Netherlands–Germany border. Both offer exceptional

geological stability and low-seismic conditions needed for the

precise measurement of spacetime distortions.

ET will employ innovative technologies such as cryogenically

cooled mirrors, high-power laser systems, and advanced

vibration-isolation systems. These developments will allow an

unprecedented sensitivity, enabling the detection of signals from

the most distant and ancient events in the Universe. More

information is available on the official Einstein Telescope

website.

Researchers from the IFJ PAN, NZ 15 will take part in the

scientific programme of the Einstein Telescope (ET), contributing

to theoretical studies, numerical relativity simulations,

gravitational wave inputs, data analysis methods, and the

development of the multimessenger astrophysics framework that

connects gravitational-wave, neutrino, and cosmic-ray

observations.

Within IFJ PAN, the group currently includes researchers who focus

on neutron star physics and their role as gravitational-wave

sources, exploring the connection between dense-matter equations

of state and observable waveforms either from compact star

oscillations or from their mergers. Complementarly, the modeling

of early universe phase transitions, formation of cosmic strings

and primordial black holes as well as quantum gravity effects are

studied in order to derive associated gravitational wave signals.

Work is also done on gravitational waves from eccentric binary

systems, the influence of spin-induced effects, and advanced data

analysis and Fisher matrix techniques used to assess parameter

estimation accuracy for future ET observations.

In the coming years, the team plans to expand its activities by

including an experimental physicist to strengthen the link between

detector technology and astrophysical data analysis.

The opportunities of the Einstein Telescope (EN)